A brief history of ransomware

Ransomware is the biggest cyber threat to businesses. First burst onto the scene in 1989, it has evolved significantly over the past few years from widespread attacks to highly targeted Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) operations affecting organizations of all sizes and sectors. This article takes a look at the evolution of the ransomware ecosystem – what it looks like today, and how it has changed over time.

1989-2014: The beginning of ransomware

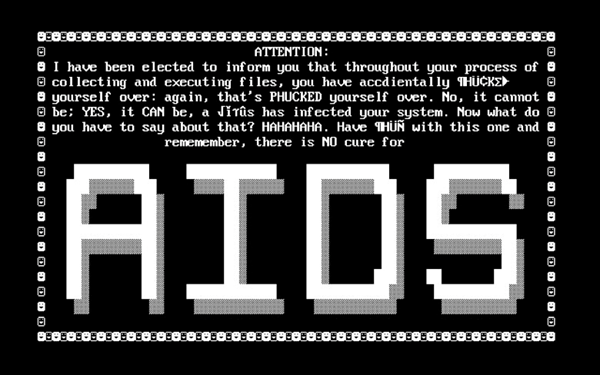

The first documented ransomware, AIDS Trojan or PC Cyborg, was delivered at the World Health Organization’s AIDS conference in 1989 using floppy disks, demanding a payment to be sent to a postal office box in Panama. This malicious code was not encrypting the files content as we know it today, but the filenames only. It was however enough to take down the systems and cause disruption. The author of the ransomware, a biologist, wanted to collect money to help advance AIDS research.

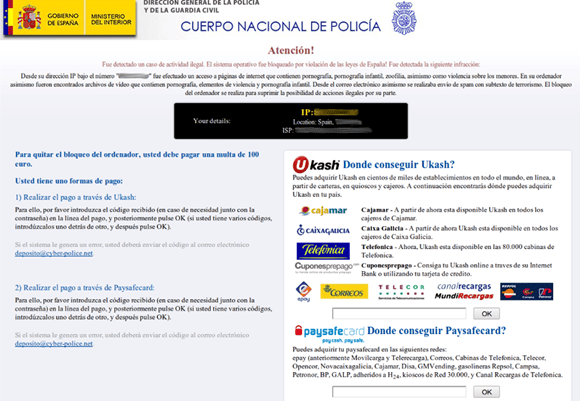

Since then, more sophisticated malware families appeared, like GpCode in 2004, spread via malspam campaigns and victims were asked to use gift cards like Ukash to pay the ransom. This malware encrypted the files much like ransomwares today but it contained cryptographic flaws which made the recovery process rather easy.

Around 2011 a new ransomware threat appeared: Reveton (the police ransomware). This malware was not encrypting the files but locking the screen of the victims, showing a threatening police warning and asking users to pay a fine with pre-paid gift cards like Paysafecard and MoneyPak. The warning was localized into different languages, using relevant police logos making this more realistic for the victims.

2014-2017: The ransomware boom

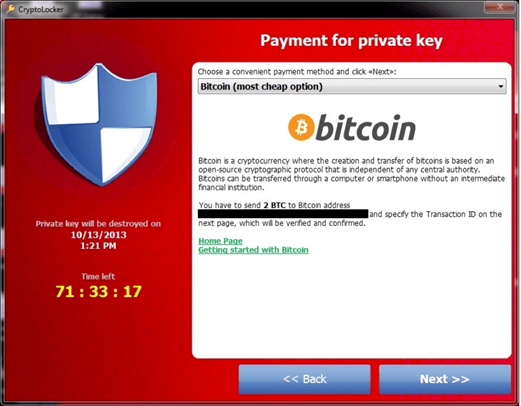

Between 2011 and 2014, most of the cybercrime ecosystem was focusing on banking botnets, because that was where the money was. However, the focus changed in 2014 when the CryptoLocker botnet was taken down, operated by “Slavik”. The botnet was taken down by the FBI in Operation Tovar with the help of cybersecurity companies like Fox-IT and CrowdStrike. Slavik operated the GameOver ZeuS botnet too – a rather big botnet -, and used some of the sub-botnets to deliver CryptoLocker, with the ability to infect many more computers than previous ransomware families.

After the takedown of both botnets, the earnings of the CryptoLocker operation were published (around 3 million USD in 9 months) and triggered a boom of new ransomware families between 2014 and 2017: CryptoWall, TeslaCrypt, CTB-Locker, TorrentLocker, WannaCry, etc. These malware families were distributed using different attack vectors operated by different threat actors using malspam campaigns, vulnerabilities, exploit kits, etc. The ransomware distribution remains widespread during this period before becoming highly targeted.

The Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) business model begins to emerge along with the birth of cryptocurrencies. These deregulated currencies became the new way of paying ransoms, a trend started by CryptoLocker in 2013. Due to the increased threat risk and impact that all these ransomware variants were causing, the NoMoreRansom initiative was set up by Europol and the Dutch police’s national cybercrime unit to help victims and organizations impacted by ransomware.

2017-2020: Game changer: targeted ransomware

Up until this time, ransomware was mostly spread through weak credential abuse, exposed unsecure services (like RDP systems), malspam and active exploit kits. The focus was on infecting any kind of victim and organization anywhere in the world. However, this scattered effort was not too effective – many victims were not paying up, partially due to anecdotes of ransomware groups not decrypting the files after the payment. So these threat groups needed a better way to monetize ransomware.

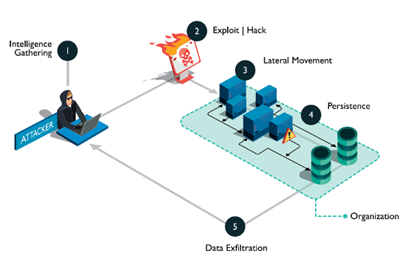

Following the trend led by Slavik and “EvilCorp” (“Dridex Group”), we started to see cybercriminals using existent infections to deploy ransomware into specific systems. Choosing specific bots to drop malware was not new, as it was used by Anunak to deploy POS malware to specific Dridex bots in the past, for instance, but it was starting to be used to deploy ransomware too. This is what is called big game hunting nowadays – by choosing high-value targets that will warrant a much bigger Return of Investment (ROI) and effort. In this case, attackers will need specific and advanced knowledge in order to perform intrusions and move laterally in a target network.

Some of the most prolific threat groups using this new approach were EvilCorp, who used Dridex infections to deliver BitPaymer, and the “TrickBot Group” (“Wizard Spider”) who use Trickbot infections to deliver Ryuk ransomware. Thanks to this new model, the tables turned. This was not new for cybercriminals, as they used to do it before, but it was the first time they were doing that with the aim of deploying ransomware. These cybercriminals were leaving behind domestic infections to target big and well-known organizations, who could pay larger ransom amounts to maximize their profit margins.

Using big game hunting was not possible for all cybercriminals, so these new ransomware variants operated by advanced threat actors were mixed with more widespread and commodity ransomware.

2020-2022: Double and triple extortion

As the pandemic hit in 2020, targeted ransomware attacks were everywhere. Domestic users were given some breathing space as the target shifted to businesses, and their remote workers. Threat actors using ransomware were performing lateral movements in the targeted organizations and deploying the malware in several systems at the same time in order to have an even bigger impact and increase the chances to make the victim pay the ransom.

Those threat actors learned from the past and, once a victim was paying the ransom, all their files were successfully decrypted, and the targeted organization could come back to “normal”. Providing a good “service” to victims was as important as infecting them, that was clear to them.

However, victims were not always paying, so threat groups managed to put more pressure into them to make them pay. At the end of 2019, the “Maze Ransomware Group” started to steal confidential information from the victims and threaten them to publish it if they did not pay the ransom. This was the beginning of the double extortion tactic. Since then, more and more threat groups have followed this idea, creating their own leak websites to publicly list their victims and expose their files if they don’t pay.

In the last years we have witnessed how threat actors are not just stealing confidential information from their victims, but they are using this information to put even more pressure on them. They are using client information to contact affected customers and inform them that their data has been stolen and that if the company X does not pay the ransom, the threat actor will publish the exfiltrated information. In some cases, they are even trying to blackmail those clients too. This is what is called triple extortion.

Another way to perform this new level of extortion is to threaten the victim to contact stock market regulators about the data breach and make their stock price dump.

2022: Targeted attacks, a commodity

In 2022, we can rarely find commodity ransomware families anymore, as targeted attacks are the new commodity. Making use of the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model, cybercriminals can get their hands on popular ransomware samples, buy stolen credentials or systems access from Initial Access Brokers (IABs) in the DeepWeb forums and markets, and deploy the malware into the targeted victim. Those Initial Access Brokers can provide enough information to know what vertical they want to attack or what country. Most of these cybercriminals just look at the company revenue to know if it is a good target for them or not.

The key to distinguish between advanced and not advanced attackers is the threat actor’s skills to keep the access, move laterally and cause the biggest impact possible. Depending on these factors, they will be more or less successful, but they don’t have to worry about the ransomware itself or how to breach the company, because that’s already provided in the DeepWeb.

Conclusions

Sometimes, besides responding to incidents and documenting Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs), we also need to take the time to look at the past to better understand the present (and future). Most cybercriminals are financially motivated and their goal is getting rich as soon as possible before they get caught. The path they follow to accomplish this objective depends a lot on how technology evolves and how the cybercrime ecosystem evolves.

Banking botnets were the way to go years ago, until CryptoLocker was taken down and the ransomware boom started. Since then, threat actors have been adapting to this new trend, evolving their toolset and techniques, and offering underground services to support this business model.

The only way to fight ransomware is making sure that security is on the budget agenda, adding resources to try to make threat actors objective less achievable: detecting stolen and leaked credentials, detecting exposed systems, knowing your enemies’ movements thanks to threat intelligence, fixing important vulnerabilities, following a good backup policy and educating employees.